Recap of March 10

As I am sure all of you are aware at this point, on Friday, March 10, 2023, the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation (DFPI) took possession of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), citing inadequate liquidity and insolvency. The DFPI appointed the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) as receiver of SVB, and the FDIC in turn created the Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara, which now holds the insured deposits from SVB. Over the course of last weekend regulators moved swiftly and took two major actions to try and contain any potential contagion: (1) they provided a guarantee to cover all deposits at SVB; and Signature Bank and (2) they put in place the Bank Term Funding Program, a generous new short-term lending facility.

Weakness in other regional banks

Although these actions certainly provided confidence to the system heading into Monday morning, March 13, investor fears the latter half of the week caused weakness in other regional banks. First Republic lost a fifth of its market share after S&P Global Ratings downgraded its credit rating to “junk.” It subsequently took a $30 billion investment from a syndicate of eleven major banks, including JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Citigroup and Truist. Given the difference in balance sheets between SVB and First Republic, this shows just how fragile the banking system can be when it comes to issues of consumer confidence.

We saw more action in the banking world this past weekend with the announcement that UBS would purchase Credit Suisse for $3.2 billion. This came at the urging of regulators and required the Swiss government to provide more than $9 billion to backstop losses that UBS may incur in taking over Credit Suisse. The Swiss National Bank is providing more than $100 billion of liquidity to UBS to help facilitate the transaction.

What questions does all of this have us asking?

After the precipitous demise of SVB and Signature Bank over the weekend followed by the swift action of regulators to try and stem the tide of contagion, we are left with a number of questions about what the knock on effects might be.

I. Has the Fed done enough to stem the tide of contagion?

The Fed has taken two major policy actions: (1) A guarantee covering all deposits of SVB and Signature Bank; and (2) put in place the Bank Term Funding Program, a generous new short-term lending facility. Although there was some positive market response with regional bank stocks market value improving early in the week, in situations like these it is never quite clear whether enough has been done. This became clear as the market value of many of the regional banks rode a roller coaster the rest of the week with First Republic even taking a $30 billion investment from eleven major banks. The collapse of SVB and Signature Bank caused a stunning shift in market expectations around Fed policy towards interest rates, but a strong core CPI reading for February this week was a reminder that the inflation issue remains front and center. Either way, it appears as though risks to increasing US interest rates have shifted to the downside.

II. What is the magnitude of unrealized losses on banks’ balance sheets throughout the system?

Higher interest rates caused a loss in value of SVB’s securities portfolio, which is a headwind faced by all banks. 450 basis points of rate hikes in a 12-month period drove $620 billion of unrealized losses on US bank balance sheets at the end of 2022. We have already seen a small erosion of core capital ratios due to unrealized losses on available for sale securities accumulated during the past year. Looking at the ~60 largest banks, we see that the CET1 capital ratio fell from 13.4% to 12.9% of risk weighted assets over the course of 2022. This seemingly still leaves banks a decent enough capital buffer to withstand further falls in value. However, what happens if the emergency liquidity facility provided by central banks proves to be insufficient and banks need to realize losses on their held to maturity securities in order to make good on their liabilities? This would compound losses and bring banks’ solvency into question.

III. What is the risk of contagion to other domestic banks or other economies?

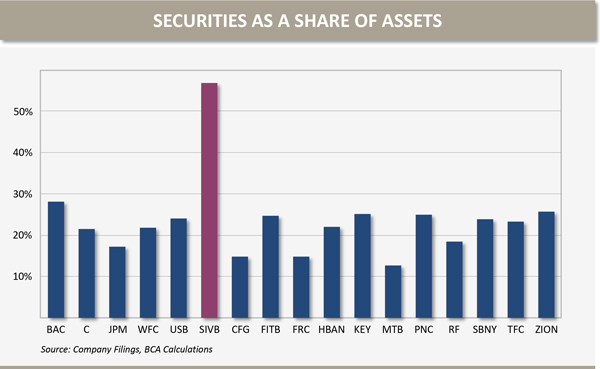

The main channel of contagion to both US banks and other economies is a loss of confidence in the system as a whole. It is difficult to predict if and when this will happen. There are a few items that give us some comfort that we might avoid it. First, the collapses of SVB and Signature Bank were due to seemingly idiosyncratic issues, large unhedged interest rate risk and large exposures to cryptocurrency, respectively. Other major banks and large regionals have a lower level of balance sheet exposure.

Source: BCA Research

Second, SVB was not subject to the Fed’s stress tests, which might have clamped down on its behaviors (maybe). Our hesitation on this point stems from the fact that the Fed had spotted issues at SVB, noting that it was using an incorrect model to evaluate interest rate risk and keeping it under supervisory review for much of 2022. In the Eurozone, the European Banking Authority takes a more expansive approach, conducting stress tests on 70 European banks covering 70% of EU banking assets. The question is whether or not the regulators would be able to do anything to correct bad behavior before markets identify it and react.

Third, and likely most important, central banks have several tools to manage contagion risks caused by problems on the liability side of banks’ balance sheets. That is, bank runs or a freezing within funding markets. We saw two of these tools employed in this scenario: (1) the expansion of deposit insurance; and (2) the extension of lending windows. This is notably different from situations involving a crisis driven by an increase in credit risk (e.g., the collapse of Lehman Brothers).

Nevertheless, there is the very real possibility that given how interconnected our financial system is, other follow-on issues will emerge that are not front and center today. Also, given how dependent our banking system is on consumer confidence, any serious degradation in consumers’ confidence that banks can meet deposit demands will have swift, negative consequences for banks (e.g., First Republic) and will likely ripple through the rest of the US and potentially, the global economy.

IV. How will other central banks respond?

For the time being it is likely that central banks will continue on their independent hiking paths as they continue to fight inflation. The European Central Bank (ECB) went ahead with its pre-announced intention and increased the deposit rate by 50 basis points last week. The Bank of England is set to raise the Bank Rate by 25 basis points this coming week.

We only need to look back to the 1999/2000 dotcom crash as a reminder that other central banks do not have to follow the Fed in lockstep when the severity of a crisis differs from country to country. During that time, while all major central banks cut interest rates, the 475 basis point cut in the US dwarfed the 150 basis point cut in the Eurozone and the 200 basis point cut in the United Kingdom.

Although it is likely (and reasonable) that the various central banks will continue down independent paths with regard to interest rate policy and inflation battles, we have started to see coordinated central bank action on the liquidity front in order to ease strains in global funding markets and dampen the effects on the supply of credit to households and businesses. Over the weekend, The Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the ECB, the Federal Reserve and the Swiss National Bank announced a coordinated action to enhance the provision of liquidity via the standing US dollar liquidity swap line arrangements. According to a press release by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “To improve the swap lines’ effectiveness in providing U.S. dollar funding, the central banks currently offering U.S. dollar operations have agreed to increase the frequency of 7-day maturity operations from weekly to daily.”

The worst case scenario is that the problems are not confined to the US banking system and are more widespread through the broader US or global economy. This more widespread scenario could be because of similar problems to SVB or, more likely, because SVB, Signature Bank, First Republic and Credit Suisse are an early indication of other unknown vulnerabilities hiding in the financial sector.

Conclusion

The specific issues leading to the collapse of SVB and Signature Bank appear to be more acute at those institutions. However, if depositors started to fear the certainty of their deposits, as they did with SVB, policymakers would likely need to take quick action to insure those deposits, stem the outflow of capital and prevent more banks from selling assets and realizing losses. While the most likely scenario is probably something between the problems being confined to a sub segment of the US banking system on the one hand and the broader US economy on the other, there is a tail risk scenario where the collapse of SVB marks the start of a broader global financial crisis. Said more simply, the US economy is likely to feel some lasting effects, which will affect the path of US monetary policy with a left-tail possibility that the knock-on impact is not contained to the United States and will be felt more broadly throughout the global financial system.

Oxford Financial Group, Ltd. is an investment advisor registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. More information about Oxford Financial Group’s investment advisory services can be found in its Form ADV Part 2, which is available upon request. The above commentary represents the opinions of the author as of 3.20.23 and are subject to change at any time due to market or economic conditions or other factors. The information above is for educational and illustrative purposes only and does not constitute investment, tax or legal advice. No offers to sell, nor solicitation of offers to buy any securities are made hereby. Solicitations of investments and any offers to sell securities, if any, will be made only through an offering document clearly identified as such. Certain of the statements in this document are forward‐looking which cannot be guaranteed. These statements are based on current views and assumptions and involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results or future performance to differ materially from those expressed or implied in such statements. The information in this presentation is for educational and illustrative purposes only and does not constitute tax, legal or investment advice. Tax and legal counsel should be engaged before taking any action. Read the disclaimers. OFG-2303-09