A core premise of private equity is that once the General Partner (GP) has executed their value-creation plan and stabilized the business at a larger and more profitable level, they will sell the company and return capital to investors. Limited Partners (LP) are always pleased to see rising net asset values, but ultimately investors care most about distributions. Similarly, the carried interest structure, where GPs share in the realized profits, creates an incentive for them to sell assets to another private equity sponsor or a strategic acquirer.

In recent years a new source of liquidity has emerged. Continuation vehicles (CVs) are where a GP sells an asset to a newly created affiliated entity. This creates liquidity for the existing portfolio, and LPs in the current fund are given an option to cash out or recommit to the new vehicle. The CV resets the holding period for the portfolio company and creates a way to bring in additional growth capital if necessary for future add-on activity.

By definition, this concept of a GP “selling to themselves” creates inherent conflicts. In fact, prior to 2020, the CV structure was associated with low-quality assets and was employed as a last resort if a GP could not identify an acceptable third-party buyer.

This has changed post COVID. With market uncertainty brought on by a rising rate environment, and a wider pricing gap between buyers and sellers, GPs have taken a fresh look at CVs and are applying a different use case for this structure. Today, CVs are a way to “sell” and retain their most successful investments or “crown jewels.” This transaction creates a distribution for the GP’s existing fund and allows the GP to continue managing one of its largest assets and collect further management fees.

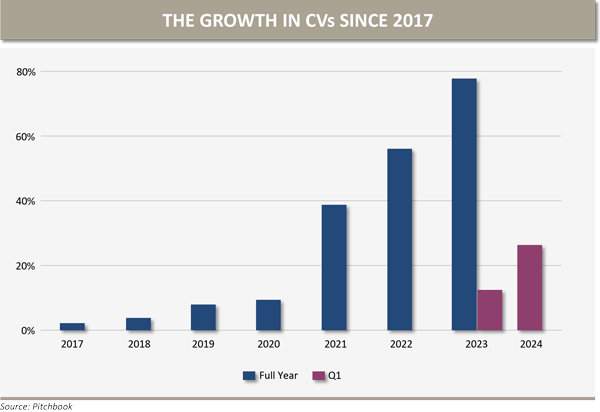

The chart below reflects the growth in CVs since 2017.

As LPs, this structure raises four core questions:

1. Is the value/pricing reasonable? GPs will typically seek out a sophisticated LP or another GP to serve as an anchor investor, but valuation is both an art and science. Potential buyers and sellers will have to assess how the established price might compare to a true third-party market-clearing level.

2. How will the GP treat their earned carried interest? Selling an asset to a CV crystallizes the carried interest, so the GP can take their compensation off the table. Our preference is to see 100% of the carried interest rolled into the new vehicle so it is “at risk” alongside CV investors.

3. Does the GP have the expertise to grow the business to that next level? Most GPs have a sweet spot with respect to a target portfolio company’s size. For example, a lower-middle-market GP has demonstrated expertise in growing business from $10 million to $50 million in earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA). If a breakout investment has reached $75 million in EBITDA, could they execute a CV and successfully grow the company to $200 million in EBITDA? Oftentimes GPs have never owned a business at this scale before. It is an open question as to whether they have the resources, networks and a value-creation plan to drive material growth in the years ahead.

4. Is the fee structure consistent with the GP’s expected value-creation? Most CVs have a discounted fee structure as compared to the market rate of a 2% annual management fee and 20% carried interest. This is primarily to incentivize capital (whether new LPs or rolling LPs) to participate in the CV. In addition, a GP may point out that the portfolio company’s management team and infrastructure have been built out over its hold period to date, i.e., the GP will not need to do the same heavy lifting that was necessary at the original acquisition.

CVs are a natural extension as GP’s seek out other ways to create liquidity and grow their AUM. While, in our view, most CVs fail to adequately answer the four questions, when a transaction is priced attractively with the proper alignment and GP expertise, our research team employs the same rigorous asset-level diligence we would do with any other co-investment opportunity. Like most financial structures the devil is in the details.