Full disclosure: I’m a relative AI neophyte, no one’s idea of a stock picker, and most of my favorite market philosophers are long-dead Austrians. With that out of the way…

I have a loosely held view that the main beneficiaries of AI will be the least obvious: boring, unloved, value stocks.

Wait… Isn’t Tech the Obvious Winner?

That’s certainly the consensus. AI and Big Tech are hot. But as the old adage goes: what’s obvious on Wall Street is obviously wrong. At the very least, it’s worth questioning.

The market’s AI narrative reeks of first-order thinking: “AI changes everything, so the companies building it must be the biggest winners.” That quickly evolves into the familiar “picks and shovels” trade — a supposedly clever second-order move that still ends with investors paying eyewatering multiples for GPU vendors. But history, and a little back-of-the-envelope math, tell a different story: it’s usually the users of a breakthrough who can capture the most value — not the ones selling the tools.

AI’s Real-World Utility: Margins, Not Magic

This whole thesis rests on a simple premise: that AI will actually make businesses more productive. Reasonable people can argue about how much — and many do — but we believe waving away the margin-boosting potential altogether feels willfully blind.

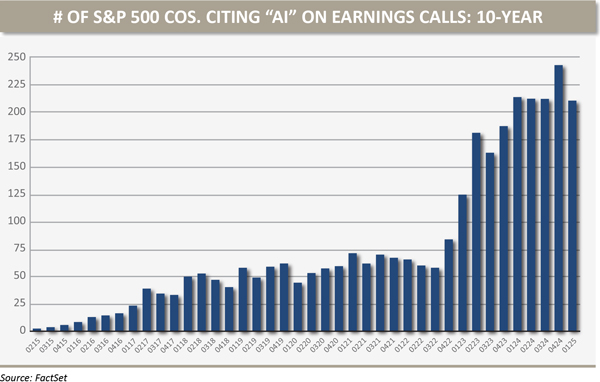

Consider that mentions of “AI” and “productivity” on public company earnings calls have surged. According to FactSet, over 210 S&P 500 company transcripts cited AI last quarter, with dozens explicitly pointing to early-stage cost reductions or efficiency gains. For instance:

- Walmart’s CFO noted in their Q1 2025 call that “our generative AI pilot in customer service has cut resolution time by over 30%, while improving satisfaction scores.”

- Accenture highlighted a 15% productivity lift in certain internal business units thanks to embedded AI copilots.

These are not pie-in-the-sky projections or VC-fueled dreamboards — they are real operational improvements, happening now, in decidedly non-glamorous sectors.

If AI Is Ubiquitous, Why Not Big Tech?

So, if AI becomes foundational to every industry — a general-purpose technology akin to electricity or the internet — why wouldn’t Big Tech dominate the value chain?

Because, I suspect, the underlying LLM (large language model) technology will become rapidly commoditized. Many of today’s supposed moats could erode as the foundational AI infrastructure becomes cheaper, more accessible, and ultimately undifferentiated.

Already, more than 1,500 open-source LLM models have been published on GitHub in the past year. Companies like Mistral, TII (the creators of Falcon) and BigScience (behind BLOOM) are pushing high-performance LLMs into the open-source ecosystem under truly permissive licenses — a sharp contrast to the closed or API-only approach of many incumbents. In a world where open weights and community-trained models rival closed systems, it’s hard to see durable pricing power or defensibility for most generalized AI platforms.

Of course, some Big Tech firms may still find ways to capture value — through proprietary data, distribution networks, or tight integration with their existing products. But the more foundational the tech becomes, the harder it is to defend margins. The kind of pricing power traditional software once enjoyed will be difficult to sustain in a world where AI becomes the baseline.

History Rhymes: When Users Win

This wouldn’t be the first time transformative technology disproportionately rewarded users, not producers. Some instructive examples:

- The internet protocol (TCP/IP): Created by government-funded academics and released as a public good. Value accrued to Amazon and Google, not to the developers of the protocol.

- Open-source software: Linux, Apache, PostgreSQL — none of these created massive fortunes for their maintainers, but they dramatically reduced IT costs for businesses worldwide.

- GPS: A U.S. military innovation that now powers logistics, agriculture, and ridesharing. It’s free to use — the value has flowed to the implementors (Uber, FedEx), not the originators.

- Browsers and email clients: Essential but mostly free, commoditized tools. Microsoft didn’t win the internet era because of Internet Explorer; Google did, by building monetized services on top of the web.

When a technology becomes ubiquitous, open-source, and commoditized, pricing power tends to disappear — and the economic value flows not to the creators, but to the users and implementers.

The Case for Value Stocks

Outcomes in investing are rarely binary, and AI is unlikely to be an exception. However, market pricing currently suggests a binary outcome: AI will drive explosive revenue growth for the “Magnificent 7,” while the rest of the economy is effectively left behind.

Valuations reflect this: large-cap growth stocks trade at 25–30x forward earnings, and large multiples of revenue in many cases. Meanwhile, our data shows classic value sectors (industrial, financial, consumer staples) trade at 8–12x free cash flow, despite stable fundamentals and improving efficiency metrics.

Let’s remember — investment returns aren’t driven by what happens, but what happens relative to what’s priced in. If AI even moderately boosts the margins of usually “boring” companies without requiring significant reinvestment, the resulting operating leverage could propel earnings far higher than currently expected.

Think about a regional bank automating compliance with AI tools, or a supply chain firm optimizing logistics with a proprietary LLM trained on internal ops data. These aren’t headline grabbers, but they’re steadily improving margins — and these companies don’t need to triple revenue to justify their current price.

Capital Intensity: A Step Backward for Big Tech?

Even if some value does accrue to the largest AI vendors, there’s a structural challenge: the capital intensity of AI. Running the most cutting-edge models isn’t cheap. It requires massive compute clusters, custom silicon, power-hungry data centers, and elite AI talent. These are not low-cost, infinitely scalable SaaS products — they’re infrastructure-heavy endeavors.

That marks a meaningful shift for Big Tech, which has historically earned wide margins by scaling software with near-zero marginal costs. AI, at least for now, looks more like oil refining — capital-intensive and resource-hungry. If that dynamic persists, it could pressure margins and erode operating leverage across Big Tech — a risk that doesn’t appear to be reflected in current market pricing.

Big Tech has the balance sheets and brainpower to absorb the current costs, no question. But whether all that spend translates into sustainably high returns — especially with open-source models closing the gap — is far less clear. My contention isn’t that these tech giants won’t grow; it’s that AI may erode the very traits that once made their business models so attractive.

A Thought Experiment: Valuations and Expectations

To put some numbers behind the idea: imagine an AI darling trading at 30x revenue as several companies currently are. If that multiple compresses over time — drifting down to a more market-like 5x revenue — then to deliver a 10% annualized return on the stock, the company’s top line must grow by more than 6x over the next decade. That’s about 20% compound annual revenue growth, sustained for ten years straight — without a stumble, margin compression, or a dilutive capital raise.

Now contrast that with a plain-vanilla industrial trading at 10x free cash flow. A bit of margin expansion and 5% annual revenue growth can get you to the same return, without needing to defy gravity for a decade.

If AI drives even modest efficiency gains, the latter starts to look a lot more attractive — and a lot less fragile.

Conclusion: Think Beyond the Obvious

This isn’t a call to abandon tech or suggest that every value stock is a diamond in the rough. But in a market swept up in AI euphoria, it’s worth asking a more fundamental question: who’s capturing the economic upside — and how much of that is already baked into market prices?

Instead of chasing the companies building the flashiest models, we believe it could be beneficial to consider the ones using them to cut costs, boost margins, and compound cash flows — all while trading like they’re stuck in a different century.

In his eerily prescient debut novel Player Piano, Kurt Vonnegut imagined a world run by machines — efficient, automated, and quietly dehumanizing. Few stopped to ask who actually benefited. As AI begins to rewire the modern corporate landscape, that same question still lingers. The biggest winners may not be those building the future, but those putting it to work.

Oxford Financial Group, Ltd. is an investment advisor with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. More information about Oxford Financial Group, Ltd.’s investment advisory services can be found in its Form ADV Part 2, which is available upon request. The information in this presentation is for educational and illustrative purposes only and does not constitute tax, legal or investment advice. Tax and legal counsel should be engaged before taking any action. This presentation has been prepared from sources and data believed to be reliable and also includes opinions that are subject to change based on changes in certain industries or market conditions. However, no representations are made as to the accuracy or completeness thereof. Past performance is not indicative of future results.OFG-2501-26