Gradually, then suddenly. The hallmarks once reserved for emerging markets—currency volatility, financial repression, unsustainable debt loads—are becoming unmistakable features of developed economies. Behind the façade of “maestro” central bankers and anodyne data releases lies a more uncomfortable reality: the rules of the game are changing. Investors raised on the post-Volcker playbook may need to start thinking less like Americans and more like Argentines, Turks or Egyptians. These are people who have long understood that currency stability is often temporary—and how beneath the surface, monetary erosion and structural fragility quietly accumulate.

The Problem: Fiscal Dominance and the Point of No Return

For decades, the United States benefited from the “exorbitant privilege” of issuing the world’s reserve currency. The Federal Reserve could cut rates to spur growth or hike them to tame inflation—tools of a flexible, rules-based regime. But that regime is breaking down. With US debt-to-GDP now above 120% and annual deficits exceeding $2 trillion, monetary policy has become reactive, not strategic. The Fed and Treasury are no longer steering; they’re managing around the constraints of debt service math.

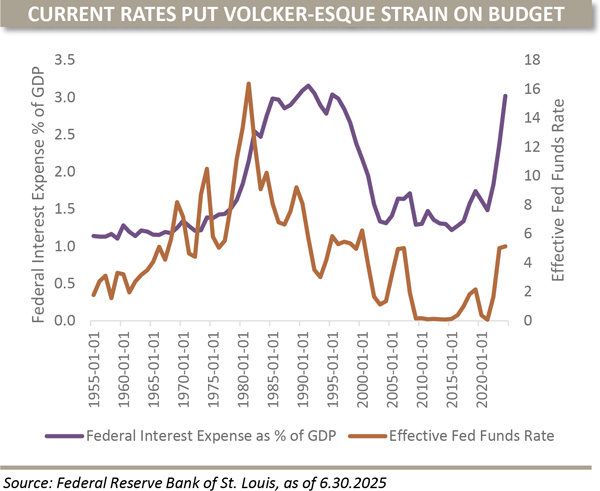

As debt accumulates, the effectiveness of monetary tightening diminishes, and its costs become structural and political. Volcker famously raised rates to nearly 20% in the early 1980s to crush inflation, but debt-to-GDP was only 30% at the time. The system could absorb the shock. Today, even modest rate hikes carry outsized fiscal consequences. Interest expense is overtaking key budget items, crowding out investment and narrowing policy options.

This is no longer abstract. The unraveling has begun. As Reinhart and Rogoff detail in This Time Is Different, when debt surpasses 100% of GDP, nations inevitably confront some mix of default, inflation or financial repression. It may not look like a default in the classical sense, but the direction of travel is obvious.

The Ideal Solution…and Why We Won’t Get It

Economics textbooks offer a clean theoretical solution: the “beautiful deleveraging” popularized by Ray Dalio. In this ideal, the debt burden is reduced gradually through a mix of moderate inflation, restrained spending and sustained real growth. Asset prices hold firm, the currency stays stable and confidence is restored.

However, achieving that outcome would require sustained real GDP growth in the mid-single digits for a decade or more just to stay ahead of the compounding burden of debt service and entitlements. There’s no historical precedent for that kind of growth, and demographics are already working against it (as discussed here: No More Mr. NICE Guy). Meanwhile, the political appetite for austerity has all but disappeared, as the swift abandonment of the ill-fated Department of Government Efficiency (“DOGE”) makes plain.

That leaves policymakers with one remaining lever: pump nominal GDP by any means available including fiscal stimulus, subsidies and industrial policy. But the arithmetic doesn’t work. The more they push for growth, the more debt they incur because this growth is fueled not by additional productivity, but by public spending. They’re pushing on a string.1

The Fed’s Trilemma: Optimize Two, Sacrifice One

At the core of today’s macro regime lies an unforgiving trade-off. The Federal Reserve can realistically sustain only two of the following three conditions at a time:

-

- Stable or rising nominal asset prices

- Manageable interest rates

- A strong, stable currency

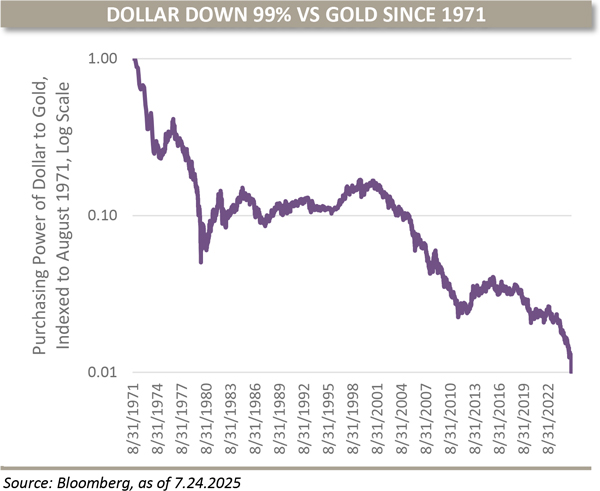

Want to suppress yields and prop up stocks, bonds and home prices? You’ll erode the purchasing power of the currency. Want to crush inflation and defend the dollar? Risk assets get smoked. As Robert Heinlein wrote, “There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch.” And when push comes to shove, policymakers almost always choose the least immediate or politically painful path: the slow debasement of the currency.

That erosion is not sudden, it is incremental and compounding. Since the US severed its final tie to gold in 1971, effectively defaulting on the Bretton Woods promise, the dollar has lost over 99% of its value in gold terms. And remarkably, the US is a positive outlier over that period. Most countries don’t sustain even a single generation of monetary stability. As Reinhart and Rogoff document in This Time Is Different:

“The median duration of a financial asset wipeout due to inflation, default or currency collapse is far shorter than people imagine. Most countries have experienced significant financial repression or outright destruction of wealth at least once every few decades.”

Investors in developed markets have long dismissed currency risk as something that happens “over there.” But in an era of towering debt, even stewards of generational wealth can no longer afford that illusion.

Where We May Be Headed

The path forward may feel unsettlingly familiar to those who have lived through emerging market instability: currency debasement, financial repression and a relentless focus on nominal asset performance as a psychological anchor for the masses. In real, inflation-adjusted terms, the compounding of wealth, especially across generations, might become far more difficult than it has been for the past half-century.

We feel as though the golden age of the 60/40 portfolio is over. Bonds, once the bedrock of portfolio safety, now look increasingly like melting ice cubes with coupon payments and principal gradually eroded by inflation. Equities, meanwhile, may continue to rise in nominal terms, sustained less by fundamentals than by excess liquidity, indexing mechanics and deeply ingrained investor preference. But in real terms, stocks may struggle to keep pace, as earnings growth lags the rate of monetary debasement.

Nominal gains may accumulate, but real wealth is being steadily diluted.

The EM Investor Playbook

While this new reality may feel jarring to US-based investors, it’s long been standard operating procedure for affluent families in much of the world.

Here’s how forward-looking investors might rethink portfolio construction for the road ahead:

-

- Hard Assets: Own things that can’t be printed. Gold and Bitcoin aren’t just hedges; they’re insurance against monetary dilution.

-

- Essential Businesses: Focus on equity in companies with durable pricing power such as energy, agriculture, infrastructure and staples.

-

- Avoid Safety Theater: Treasuries, annuities and high-grade bonds may feel safe but may deliver negative real returns.

-

- Diversifiers: Seek uncorrelated and capital-efficient strategies such as trend-following and global macro.

-

- Maintain Liquidity: Volatility can breed opportunity. Flexibility may be worth more than ever.

-

- Short the Currency (Tactfully): Finance real asset purchases, such as homes, with fixed-rate debt where appropriate, and while you still can.

These aren’t bets against the system. They’re acknowledgments of how the system works—and practical steps to stay ahead of it.

Conclusion: Evolve or Erode

For the past four decades, investors were rewarded for trusting the system—owning broad indexes, holding duration and betting on disinflationary growth as the default. That regime may be over—or at least in retreat.

The next era could reward investors who adapt—those who grasp incentive structures, respect structural constraints and navigate with pragmatism and historical perspective.

You don’t need to bet on collapse. But it may be wise to retire the assumption that the future will resemble the past. In a world defined by policy distortion and monetary erosion, we believe financial asset-heavy portfolios are unlikely to be the obvious winners they were in the preceding decades.

We’re all emerging market investors now. In our view, it’s time to start thinking—and allocating—accordingly.

1See The Mandibles: A Family 2029-2047 by Lionel Shriver for a fictionalized – though increasingly recognizable – version of this dynamic taken to its logical conclusion.

Oxford Financial Group, Ltd. is an investment advisor with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. More information about Oxford Financial Group, Ltd.’s investment advisory services can be found in its Form ADV Part 2, which is available upon request. The information in this presentation is for educational and illustrative purposes only and does not constitute tax, legal or investment advice. Tax and legal counsel should be engaged before taking any action. This presentation has been prepared from sources and data believed to be reliable and also includes opinions that are subject to change based on changes in certain industries or market conditions. However, no representations are made as to the accuracy or completeness thereof. Past performance is not indicative of future results.OFG-2508-2